What do you think?

Rate this book

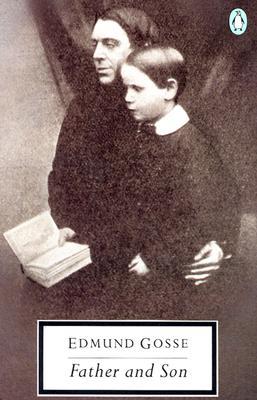

201 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1907

Here was perfect purity, perfect intrepidity, perfect abnegation; yet here was also narrowness, isolation, an absence of perspective, let it be boldly admitted, an absence of humanity. And there was a curious mixture of humbleness and arrogance; entire resignation to the will of God and not less entire disdain of the judgment and opinion of God.

[H]e allowed the turbid volume of superstition to drown the delicate stream of reason.

He who was so tender-hearted that he could not bear to witness the pain or distress of any person, however disagreeable or undeserving, was quite acquiescent in believing that God would punish human beings, in millions, for ever, for a purely intellectual error of comprehension.

Glimpses of the Wonderful: The Life of Philip Henry Gosse 1810鈥�1888 by Ann Thwaite

In the Days of Rain, Rebecca Stott鈥檚 memoir of growing up in the Plymouth Brethren in the 1960s

"After my long experience, after my patience and forbearance, I have surely the right to protest against the untruth (would that I could apply to it any other word!) that evangelical religion, or any religion in a violent form, is a wholesome or valuable or desirable adjunct to human life. It divides heart from heart. It sets up a vain, chimerical ideal, in the barren pursuit of which all the tender, indulgent affections, all the genial play of life, all the exquisite pleasures and soft resignations of the body, all that enlarges and calms the soul are exchanged for what is harsh and void and negative. It encourages a stern and ignorant spirit of condemnation; it throws altogether out of gear the healthy movement of the conscience; it invents virtues which are sterile and cruel; it invents sins which are no sins at all, but which darken the heaven of innocent joy with futile clouds of remorse. There is something horrible, if we will bring ourselves to face it, in the fanaticism that can do nothing with this pathetic and fugitive existence of ours but treat it as if it were the uncomfortable ante-chamber to a palace which no one has explored and of the plan of which we know absolutely nothing."