August 24, 2013

A fairly common mistake made by authors is failing to be familiar with their genre. They end up retreading old ground and relying on long-dead cliches because they aren't aware of what's already been done. So, it behooves an author to get some familiarity with the genre he intends to work in, to ensure that he isn't just writing the same old story over again.

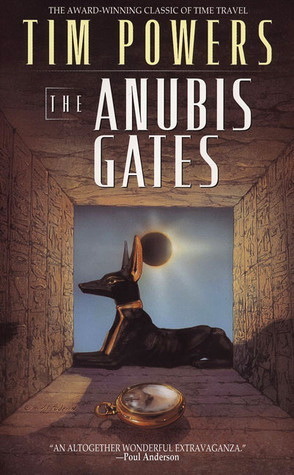

In that spirit, I thought I'd check out this award-winning early piece of Steampunk. It was a rough start. One of the first red flags in an author's prose is how often they use 'almost', 'seemed' or worst of all 'almost seemed' in their descriptions and metaphors. Such words are meaningless filler, and are usually a sign that the author is not comfortable with his own figurative language, or is trying to seem mysterious without really knowing how to do it.

We're barely a page in before Powers gives us 'a musty fetor . . . almost shockingly incongruous when carried on the clean breezes of Hampstead Heath'. Almost shockingly incongruous, but not actually shockingly incongruous. But, if it isn't actually shockingly incongruous, why not tell us what it really is like? Why use a phrase that almost describes the situation, but not quite? What is the benefit to this imprecision?

Of course, in most cases, it is just 'shockingly incongruous', and the 'almost' just happened to slip in there for no reason at all.

From there we move on to the conflicted metaphors:

"His cloak flapping behind him in the wind like the wing-case of some gigantic insect"

'Like some' is another meaningless phrase to look out for in figurative language. It's meant to sound mysterious, but really, it's just filler. Beyond that, to anyone actually familiar with insect wing-cases, this metaphor just doesn't make sense, because wing cases are rigid and during flight. They don't flap. In the case of the scarab, which I assume Powers is trying to evoke here in his Egyptian magic story, they're also shiny.

Also, why does it have to be a 'gigantic' insect? Because he's a person, and people are bigger than insects? Figurative language already has that covered. If you say 'his gaze darted about like a viper's', you don't have to continue 'but a viper with hair, and external ears, and lacking scales, and also much larger than a normal one, and with limbs and no tail, and without the capacity for natural poison'. There's a reason that explaining a metaphor that way is often done as a joke--it's simply not necessary.

Here's another one:

"[The tent] looked, thought Fikee, like some huge nun in a particularly cold-weather habit, crouched beside the river in obscure devotion."

Can you picture that? Does that produce a clear and effective image in your mind, or a rather confused muddle? For me, it was definitely muddle. These two metaphors appear on the same page, along with another one about a smile being 'like a section of hillside falling away to expose old white stone', which isn't so bad, but that's a lot of trying-too-hard similes to cram on just one page.

Next page.

"Romany intoned, his voice becoming deeper as though trying to wring an echo out of the surrounding carpets"

'As though' is another vague little bit we want to be careful about when we write. I don't think the verb 'wring' works there at all. Are you imagine someone twisting carpets (with their voice) in order to try to squeeze some extra echoes out of them, because that's what this description paints into my mind, and it is not remotely working.

A few pages on, and we break suddenly into a long stretch of story exposition straight from the narrator about all this stuff that happened before, to set up the story. So, why start off with a mysterious intro where your characters are mumbling odd references to events, if you're going to explain them all a few pages later? That's a pretty quick way to kill all the mystery you had just been trying to build up.

Then, the characters themselves start delivering long pieces of story exposition to one another, even though they all know these things already!

"I'm sure you haven't forgotten how you suffered after playing with the weather at the Bay of Aboukeer three years ago."

So yeah, that's definitely enough of this book.

In that spirit, I thought I'd check out this award-winning early piece of Steampunk. It was a rough start. One of the first red flags in an author's prose is how often they use 'almost', 'seemed' or worst of all 'almost seemed' in their descriptions and metaphors. Such words are meaningless filler, and are usually a sign that the author is not comfortable with his own figurative language, or is trying to seem mysterious without really knowing how to do it.

We're barely a page in before Powers gives us 'a musty fetor . . . almost shockingly incongruous when carried on the clean breezes of Hampstead Heath'. Almost shockingly incongruous, but not actually shockingly incongruous. But, if it isn't actually shockingly incongruous, why not tell us what it really is like? Why use a phrase that almost describes the situation, but not quite? What is the benefit to this imprecision?

Of course, in most cases, it is just 'shockingly incongruous', and the 'almost' just happened to slip in there for no reason at all.

From there we move on to the conflicted metaphors:

"His cloak flapping behind him in the wind like the wing-case of some gigantic insect"

'Like some' is another meaningless phrase to look out for in figurative language. It's meant to sound mysterious, but really, it's just filler. Beyond that, to anyone actually familiar with insect wing-cases, this metaphor just doesn't make sense, because wing cases are rigid and during flight. They don't flap. In the case of the scarab, which I assume Powers is trying to evoke here in his Egyptian magic story, they're also shiny.

Also, why does it have to be a 'gigantic' insect? Because he's a person, and people are bigger than insects? Figurative language already has that covered. If you say 'his gaze darted about like a viper's', you don't have to continue 'but a viper with hair, and external ears, and lacking scales, and also much larger than a normal one, and with limbs and no tail, and without the capacity for natural poison'. There's a reason that explaining a metaphor that way is often done as a joke--it's simply not necessary.

Here's another one:

"[The tent] looked, thought Fikee, like some huge nun in a particularly cold-weather habit, crouched beside the river in obscure devotion."

Can you picture that? Does that produce a clear and effective image in your mind, or a rather confused muddle? For me, it was definitely muddle. These two metaphors appear on the same page, along with another one about a smile being 'like a section of hillside falling away to expose old white stone', which isn't so bad, but that's a lot of trying-too-hard similes to cram on just one page.

Next page.

"Romany intoned, his voice becoming deeper as though trying to wring an echo out of the surrounding carpets"

'As though' is another vague little bit we want to be careful about when we write. I don't think the verb 'wring' works there at all. Are you imagine someone twisting carpets (with their voice) in order to try to squeeze some extra echoes out of them, because that's what this description paints into my mind, and it is not remotely working.

A few pages on, and we break suddenly into a long stretch of story exposition straight from the narrator about all this stuff that happened before, to set up the story. So, why start off with a mysterious intro where your characters are mumbling odd references to events, if you're going to explain them all a few pages later? That's a pretty quick way to kill all the mystery you had just been trying to build up.

Then, the characters themselves start delivering long pieces of story exposition to one another, even though they all know these things already!

"I'm sure you haven't forgotten how you suffered after playing with the weather at the Bay of Aboukeer three years ago."

So yeah, that's definitely enough of this book.